The rapid increase in scale and scope of community health worker (CHW) programmes highlights a clear need for guidance to help programme providers optimise programme design. A new World Health Organization (WHO) guideline in this area [1] is therefore particularly welcome, and provides a complement to existing guidance based on practitioner expertise.[2] The authors of the WHO guideline undertook an overview of existing reviews (N=122 reviews with over 4,000 references included), 15 separate systematic reviews of primary studies (N=137 studies included), and a stakeholder perception survey (N=96 responses). The practitioner expertise report was developed following a consensus meeting of six CHW programme implementers, a review of over 100 programme documents, a comparison of the standard operating procedures of each implementer to identify areas of alignment and variation, and interviews with each implementer.

The volume of existing research, in terms of the number of eligible studies included in each of the 15 systematic reviews, varied widely, from no studies for the review question “Should practising CHWs work in a multi-cadre team versus in a single-cadre CHW system?” to 43 studies for the review question “Are community engagement strategies effective in improving CHW programme performance and utilization?”. Across the 15 review questions, only two could be answered with “moderate” certainty of evidence (the remainder were “low” or “very low”): “What competencies should be included in the curriculum?” and “Are community engagement strategies effective?”. Only three review questions had a “strong” recommendation (as opposed to “conditional”): those based on Remuneration(do so financially), Contracting agreements(give CHWs a written agreement), and Community engagement(adopt various strategies). There was also a “strong” recommendation not to use marital status as a selection criterion.

The practitioner expertise report provided recommendations in eight key areas and included a series of appendices with examples of selection tools, supervision tools and performance management tools. Across the 18 design elements, there was alignment across the six implementers for 14, variation for two (Accreditation– although it is recommended that all CHW programmes include accreditation – and CHW:Population ratio), and general alignment but one or more outliers for two (Career advancement– although supported by all implementers, and Supply chain management practices).

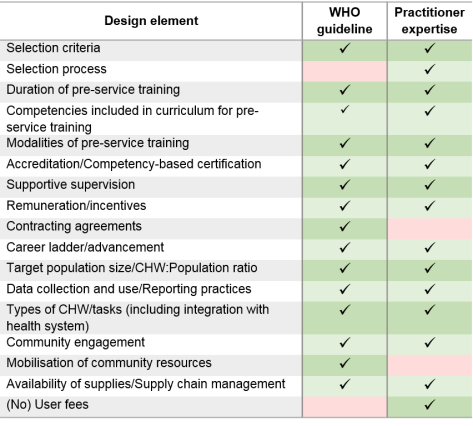

There was general agreement between the two documents in terms of the design elements that should be considered for CHW programmes (Table 1), although notincluding an element does not necessarily mean that the report authors do not think it is important. In terms of the specific content of the recommendations, the practitioner expertise document was generally more specific; for example, on the frequency of supervision the WHO recommend “regular support” and practitioners “at least once per month”. The practitioner expertise report also included detail on selection processes, as well as selection criteria: not just what to select for, but how to put this into practice in the field. Both reports rightly highlight the need for programme implementers to consider all of the recommendations within their own local contexts; one size will not fit all. Both also highlight the need for more high quality research. We recently found no evidence of the predictive validity of the selection tools used by Living Goods to select their CHWs,[3] although these tools are included as exemplars in the practitioner expertise report. Given the lack of high quality evidence available to the WHO report authors, (suitably qualified) practitioner expertise is vital in the short term, and this should now be used in conjunction with the WHO report findings to agree priorities for future research.

Table 1: Comparison of design elements included in the WHO guideline and Practitioner Expertise report

— Celia Taylor, Associate Professor

- World Health Organization. WHO guideline on health policy and system support to optimize community health worker programmes. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2018.

- Community Health Impact Coalition. Practitioner Expertise to Optimize Community Health Systems. 2018.

- Taylor CA, Lilford RJ, Wroe E, Griffiths F, Ngechu R. The predictive validity of the Living Goods selection tools for community health workers in Kenya: cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018; 18: 803.